My Son Doesn't Remember His Cancer Battle

Last month, my younger son and I were in the car on a gray, icy evening. We were on our way to his swim lesson. It felt dark, even for winter, and I was winding through some back roads and smaller neighborhoods. I was pretty focused on driving when he asked me to play “Got My Mind Set On You” by George Harrison.

The ability to play requested songs at will is both good and bad. Usually I don’t mind, but he tends to request the same songs over and over. There are a few songs I need a multi-year break from, like “Crocodile Rock” by Elton John and “Holding Out for a Hero” by Bonnie Tyler. This Harrison solo hit almost reached banned-list levels during our many drives to the hospital on the south side of Chicago. I laughed, joked about how he used to listen to it all the time, and put it on as we drove past a frozen pond.

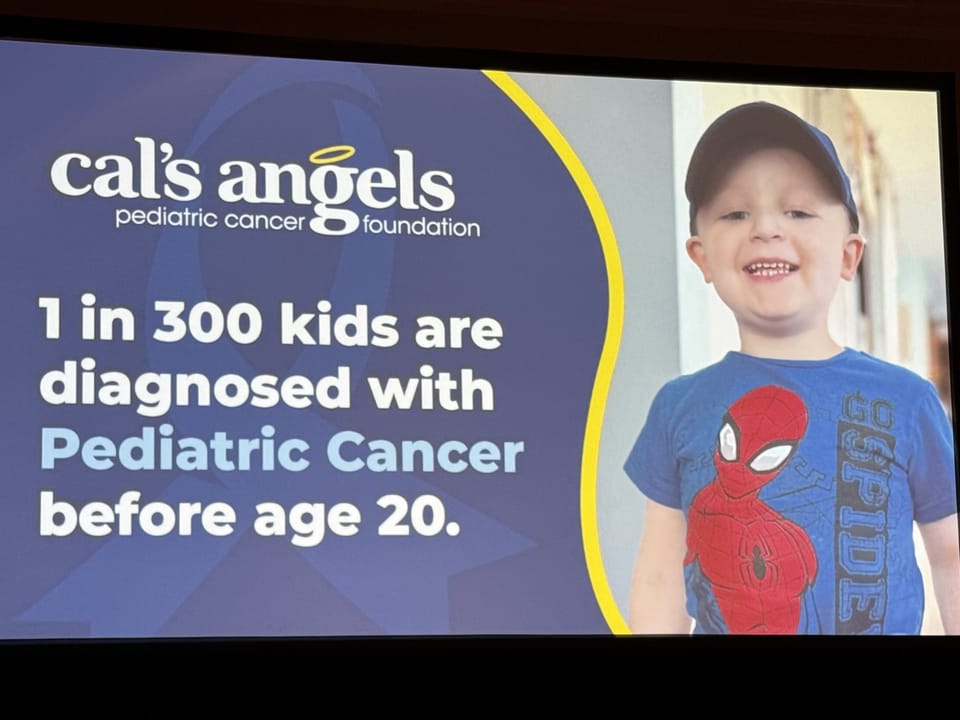

Our boy was 2 and a half when he was diagnosed with leukemia. He’d been alive for 28 mostly uneventful months, doing normal kid things like crawling then walking, learning to sleep properly, going to daycare, crying occasionally, until all of the sudden, he started having unexplained bruising and a series of crappy little viruses. We took him to the emergency room at the hospital nearest to our house at first, but he was quickly transferred to Comer, the children’s hospital at the University of Chicago. Comer is about 25 miles from us, which translates to anywhere between 40 minutes to an hour and a half of driving time, depending on traffic.

We were often driving in during morning rush hour. While this wasn’t ideal, traffic was the lesser evil between that and a long day of toddler hunger. He would have to fast before sedation appointments, so we usually tried to get one of the first time slots of the day, if possible.

A lot of his chemo appointments required sedation because toddlers undergo general anesthesia for lumbar punctures. For teens and adults, patients can remain awake with local anesthesia because they have the ability to remain completely still while a needle is inserted into their spinal column, similar to an epidural. There’s no expectation for children under a certain age (I’m not sure what that age actually is) to have this ability. They would take out spinal fluid to test and replace it with the same amount of methotrexate, a chemo drug. By the end of his treatment, our little guy had 19 lumbar punctures and 22 (I think) sedations.

He used to ask for “Got My Mind Sep on Youp” about one hundred and fifty thousand times on those drives. We would usually get through about 5 consecutive plays before he fell asleep. He became a champion car sleeper. When I tried to remind him of this on the way to his swim lesson a few weeks ago, he laughed and said, “oh yeah!” And after being quiet for another moment, he said, “I don’t remember that. I forgot about this song until the other day.” It felt like a punch in the gut.

Thankfully I was able to hide my initial reaction. I started to carefully feel around.

Me: “Do you remember being sick?”

Him: “Yeah.”

“Do you remember what it felt like in your body?”

“Yeah, my throat was kinda sore, and my nose was stuffy.”

Realizing he was talking about the cold he just got over, I tried again.

“Oh yeah, that never feels good. What about the big sick? When you had cancer? Do you remember what that felt like?”

“Yeah, pretty much the same.”

I held it together, but I was shocked. He didn’t remember any of it. I don’t know why I was so surprised by the revelation. I think he has flashes of memories, but nothing sustained. He was 2 and a half at diagnosis, and he’s only 5 now.

Ok clearly, I am happy he doesn’t remember suffering, and I’m happy he doesn’t have cancer as a root part of his identity, despite it being the biggest thing to happen to him so far in his young life. I’m also certain he’s retained more about the treatment and recovery than he’s letting on, in a “body keeps the score” kind of way. All of this can be true while also bewildering me that this thing that happened to HIM remains in MY awful memories, as well as those of his dad and his older brother.

I guess things like this happen all the time. Babies don’t remember how terrible the process of birthing them is. Granted, it’s the mother’s body doing all of the work, but being born is a traumatic experience each person has and then does not remember. Small children endure illnesses, accidents, all sorts of stuff, without retaining memories of the events.

It took me a little time to figure out what exactly it was that upset me about this revelation. I had been counting on there being a silver lining to this whole ordeal. I think the only thing that was helping me get past my anger about this stupid disease was the fact that he would be able to learn and grow from it. I had been assuming that, even after all of my cynicism and determination to not assign meaning where there was none, he would’ve learned something from his cancer battle. He would go through the trials of treatment and come out mentally tougher, stronger, better in some tangible way. I thought he would have a better perspective and have a deeper understanding of or respect for his body. But none of that will be automatic. We, his parents, will still have to teach him all of that stuff.

But then, the silver lining shined through. A couple of weeks later, we were headed to a check up, and he started asking about cancer. We know someone who recently died of cancer, and my boy made a startling connection: he could’ve died. He asked me if that was true, and I couldn’t lie. “Yes,” I said. “If we’d have caught it any later, you could’ve died.” I got to explain to him how amazing he was and is, as well as how thankful we all are for him. He was quiet a minute, awed by this new knowledge, maybe a little awed by himself. He asked a few more questions, and while he may not remember the specifics, this experience can still be part of him, one conversation at a time.

Member discussion